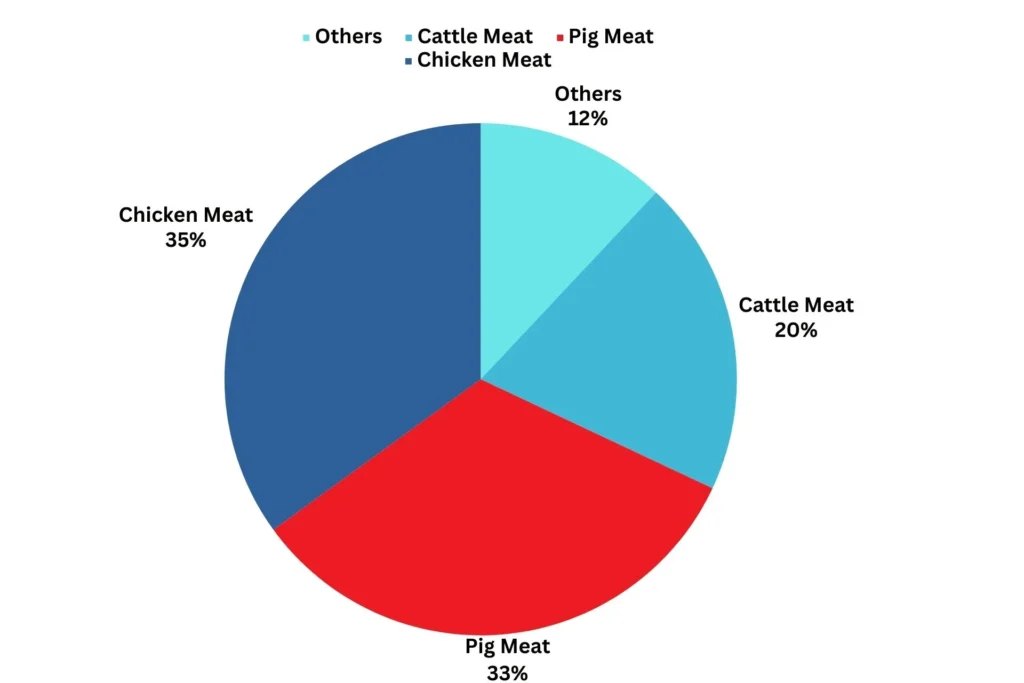

Pork has got to be the most polarizing meat—possibly the most polarizing food. Pork is, by some reckoning, the most popular meat in the world, accounting for more than a third of global meat consumption. Yet, at the same time, about a third of humanity studiously avoids eating pigs.

I cannot find any complex data on that last point; that’s a guess. But Islam, of course, strictly forbids eating pork. Hinduism is not wild about it. It’s safe to say that a large share of humanity thinks this trendy food is inherently unclean.

Why?

Nobody knows why. You might have a reason why you regard pork as unclean. Still, I’m here to tell you that anthropologists, archaeologists, and theologians have long argued about the historical origins of the pork taboo. There needs to be a clear scholarly consensus on the matter. Or rather, there is a consensus that historically, we don’t know where the pork taboo comes from. We need more help from the primary sources. Here in the Torah is where we first see the pork taboo codified in Abrahamic religious law—Leviticus and Deuteronomy, both written down somewhere in the first millennium B.C.E. Ancient Jewish law says pork is sour because pigs have a cloven hoof but don’t chew their cud, and what does that even mean? Well, “cloven hoof” means a hoof divided into multiple toes. Here’s a horse hoof—it’s all one piece. It has no toes. Here’s a deer hoof. It’s got various toes. It is cloven. Cows, goats, and sheep all have cloven hoofs, and ancient Israelites had no problem eating cows, sheep, and goats. Why? Because in addition to having a cloven hoof, they also chew their cud. And what does that mean? Well, one of the most significant differences between you and me and Goat here is that Goatee can digest grass and other foods comprised primarily of cellulose.

Cellulose is this massive sugar that makes up the main structural bulk of most plants, and we cannot digest it. It’s just fiber. It passes right through us. But ruminants, like Goatee, swallow grass whole. Bacteria in their guts start fermenting or breaking down the cellulose and then comes the gross part. Goatee barfs up some of that fermented grass and then chews on it to break it down further before swallowing it again. This is what it means for an animal to “chew the cud.” Pigs don’t do that. Pig and human digestive systems are very similar. They eat what we eat.

Leviticus and Deuteronomy say pork is sour because pigs have a cloven hoof but don’t chew their cud. This book sounds very little about why that is bad and is even less helpful. The Quran here says that, unless you’re starving to death, the flesh of swine is forbidden, along with carrion and blood, but some people find a context clue there.

Carrion is rotten meat, usually from an animal that died on its own instead of you slaughtering it. And carrion is particularly likely to harbor dangerous pathogens and toxins. Likewise, blood is particularly likely to have pathogens. That said, you can kill them by cooking them, just like you can with any freshly slaughtered animal product. People eat blood all the time, but a lot of people look at this list and assume the prohibition against pork must have been a kind of ancient health and safety code. This theory gained much traction in the 19th century when scientists first linked the parasitic disease trichinosis and the roundworms often found in undercooked pork.

Trichinosis was pervasive in Europe and the Americas in the 19th century. At that historical moment, intellectuals in the West were eager to reconcile religious teaching with their newfound scientific knowledge. And the new understanding of trichinosis imbued a kind of scientific logic into the Old Testament, which was very attractive to people at the time. But more recent scholarship casts a lot of doubt on the trichinosis theory.

The American anthropologist Marvin Harris wrote a very influential book on meat taboos in the 1980s. “My contention,” he writes, “is that pork is not particularly noteworthy as a cause of illness in humans. Every household animal carries a risk to human health. “That much, of course, is indisputably true, and it may have been even more true in the ancient world before we had vaccines for things like anthrax. Anthrax is a horrible bacterial infection that herd animals like cattle and sheep can pass to humans.

There is no evidence that trichinosis was particularly pervasive in the ancient Middle East, and there is no evidence that ancient Middle Easterners even knew of its existence. In contrast, there is evidence that older people understand anthrax. Anthrax may have been the fifth plague of Egypt discussed in the Book of Exodus here, and Homer may have been talking about anthrax in the Iliad. There’s nothing like that for trichinosis, and Harris argues there’s a reason for that.

Meat parasites cause relatively mild illnesses in people. Most cases are asymptomatic, and the more severe problems can take years to unfold. It’s not like a poison that kills you within hours of ingesting it. It would have been hard for ancient people to perceive any link between meat and the parasitic diseases it can sometimes cause. And, of course, there’s no particular evidence that trichinosis was terrible in the Middle East; there’s no specific evidence that trichinosis was any worse than any other parasitic disease caused by any other meat. Trichinosis was terrible in 19th-century Europe and America when this theory was hatched. Harris argues that this is a simple case of modern people projecting their own experiences onto the lives of ancient people.

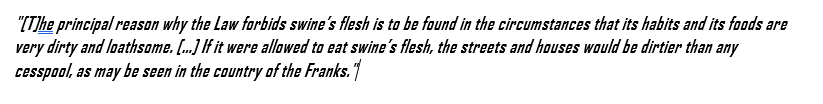

One of the earliest written arguments for why pork is wrong comes from the Middle Ages—from Maimonides. Maimonides was a philosopher who bridged the Jewish and Islamic worlds. He was a Sephardic Jewish Rabbi serving an Islamic ruler—Salah ad-Din Yusuf, or Saladin as he’s known here in the West. Maimonides was Salidin’s court physician in Egypt, and here’s what he wrote about the pork taboo about 800 years ago.

He’s talking nonsense about the Crusaders. Indeed, pigs are more conspicuously gross than most farm animals. They eat anything. They eat trash, they eat roadkill, they even eat human excrement. And they wallow around in the mud, potentially even their excitement. Is this appetizing to you? Probably not. But here’s the big question: Humans are universally revolted by filth. They are not widely appalled by pigs, and why not? One explanation may be that pigs do not universally love filth.

Pigs only resort to filth when we humans leave them no other option. This right here is the theory that Marvin Harris finds most persuasive. The ancient Middle East used to have many more trees, and when wild or domesticated pigs hang around in forests, they’re not nearly as gross. They root around at the base of trees for seeds, nuts, truffles, and things that you and I would be happy to eat. And they don’t need to wallow in the mud because they have shade.

Contrary to what the expression “sweating like a pig” would lead you to believe, pigs have no sweat glands. They have tiny lungs, so panting is not an excellent way for them to shed excess heat. In hot, sunny climates, like here in the American South, the only way for pigs to relax is to cover themselves in mud. Given the option, they’ll wallow in clean mud, but if they have to, they will bask in their excrement.

The theory goes that throughout the Iron Age, population growth in the Middle East resulted in deforestation and desertification. Pigs started to have to wallow to stay calm. Then came urbanization—thousands and thousands of humans living on top of each other and filling their streets and their city dumps with food scraps and people poo, all of which attracted pigs who were more than happy to make use of those discarded calories. As people in the Middle East increasingly came to see pigs in this new, unflattering context, they started to view pork as inherently unclean. And what’s worse is that pigs in this context may have come to compete with humans for food because pigs can’t eat grass.

They like the same kinds of foods we eat—like, you know, grains. Ancient Rome’s environment was less arid and more prosperous in food. Pigs and humans didn’t compete. Instead, urban pigs cleaned the streets of waste and converted it into delicious protein. That exact natural synergy helped make pork the favorite meat of rapidly urbanizing China to this day. Harris argues that pigs became gross and uneconomical in the comparatively arid Middle East—a double whammy.

The religious prohibitions followed a pretty persuasive argument. But there are counter-arguments. Goats also eat absolutely anything, including poop. Jews and Muslims have no religious opposition at all to eating goats, nor do they have any problem eating chicken, despite chicken coops being almost as gross as pig styes and chickens not being able to live on grass either. Those chickens are eating grain that I could be eating instead directly. They’re competing with me, but less than pigs would.

Some more recent scholarship indicates that chickens may have supplanted pork in the Middle Eastern diet because they do what pigs do, only better in the 2015 paper from the archaeologist Richard Redding at the University of Michigan. He argues that chickens can live in cramped urban spaces like pigs.

They convert food scraps into protein, but they do it more efficiently. They make eggs in addition to meat—pigs don’t do that. And chickens are smaller, which means you can just kill one, cook it, and eat the whole thing immediately. That’s a big bonus in a hot climate where meat goes fast once you’ve slaughtered the animal. Redding argues that chickens were better suited to the Middle East than pigs were—they got there later, and when they did, they supplanted pigs. But if that were true, why would you need a religious prohibition against pigs? Wouldn’t people naturally do the thing that worked better?

One more recent archaeology shows that pig eating never really stopped in the Middle East, and it wasn’t just limited to non-Israelites, like the Philistines. Ancient Jews in various parts of the region ate pigs, which makes sense, right? Nobody makes laws against things that nobody is doing. What’s clear is that once the pork taboo took hold, it became a way for people to distinguish themselves from others. Indeed, this is another pretty recent paper I’ve been showing you where archaeologists found Israelites from the Northern Kingdom were probably still eating pork when they migrated into the Southern Kingdom around the turn of the 7th century B.C.E. The law in the Torah might have been a mechanism of assimilating these northern Jews into the southern culture that chewed pork. In time, the pork taboo became a way for Israelites to distinguish themselves from the Romans. And then it became a way for the Muslims, who inherited the Abrahamic tradition, to differentiate themselves from, say, those dirty crusading Franks with their filthy streets.

But where the pork taboo first came from, No one still doesn’t know.

PORK TABOO